Kalmeshwar's Unseen Past: How Vidarbha’s Town Shaped History and Industry

- Pranay Arya

- Nov 15, 2025

- 13 min read

The region around Kalmeshwar carries within its landscape layers of settlement, transformation, and economic shifts that span over two millennia.

Located approximately 25 kilometres from Nagpur in Maharashtra's Vidarbha, this taluka headquarters occupies land historically connected to trade routes, river valleys, and the succession of dynasties that shaped central India.

The town itself emerged as a significant settlement only in recent centuries, yet the territory has held religious, agricultural, and strategic importance for generations.

Today, Kalmeshwar stands as a place where ancient archaeological evidence coexists with modern industrial infrastructure, where agricultural traditions persist despite profound challenges, and where medieval cultural practices continue alongside contemporary development projects.

Ancient Settlements and Medieval Foundations

The prehistoric and early historical landscape of Kalmeshwar taluka reveals a pattern of human settlement reaching back thousands of years.

Archaeological evidence from the Ubali area, situated on the Kalmeshwar-Mohpa road, documents the presence of megalithic burial structures dotted with cairns and cairn circles typical of the Iron Age.

The mound formations visible in this region represent multiple periods of occupation, with the Ubali site falling within the Deccan Trap formation of the Chandrabhaga River basin.

This river system, traversing the region with its network of water channels, supported early agricultural communities that selected elevated riverbank sites for their settlements.

The Chandrabhaga flows through the eastern portions of Kalmeshwar taluka before joining the Wardha River. The region's landscape, characterised by semi-arid conditions with minimal soil cover in certain areas, nonetheless contained sufficient water resources and fertile plains to sustain populations engaged in mixed pastoral and agricultural economies during the Iron Age period.

The megalithic sites of Vidarbha, including those within or near Kalmeshwar, represent a cultural horizon dating to approximately the 7th and 5th centuries before the common era, connecting the region to broader patterns of Iron Age settlement across the Deccan Trap formation.

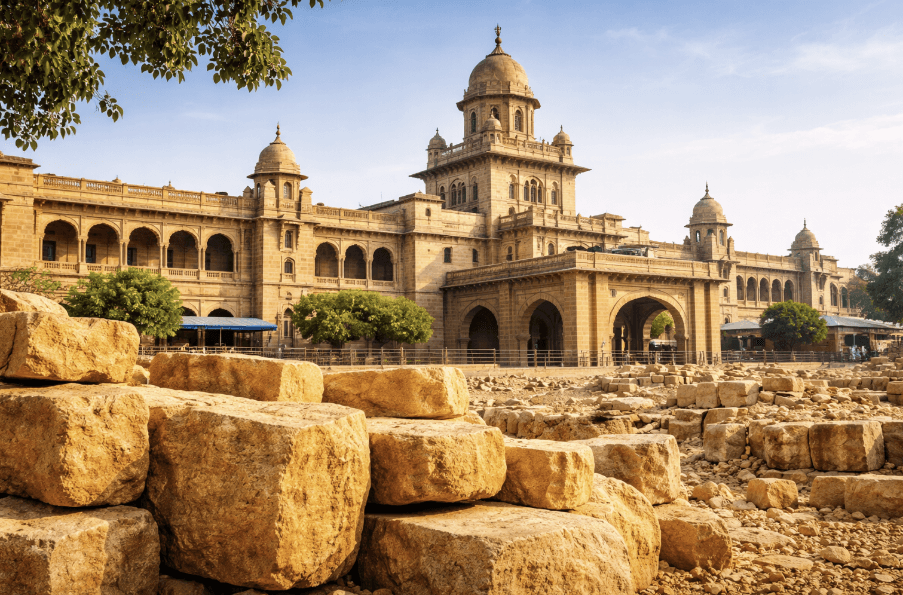

The medieval period witnessed the integration of Kalmeshwar into the religious and political frameworks that transformed Vidarbha under successive dynasties.

The architectural traditions emerging during the Vakataka period, which exercised dominion over the region from the mid-3rd to early 6th centuries, established patterns that would characterise the entire region. The nearby Trivikrama Temple of Ramtek, constructed between 420 and 450 CE under the patronage of Vakataka queen Prabhavati Gupta, exemplifies the stone temple construction innovations developed during this era.

The architectural vocabulary evolved through the succeeding centuries under the Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas, and, eventually, the Yadava dynasty. The Yadavas, who rose to independent power in 1187 CE under Bhillama V and established their capital at Devagiri (modern Daulatabad), ruled extensive territories stretching from the Tungabhadra to the Narmada rivers. This dynasty sponsored the development of the Hemadpanti architectural style, named after the royal administrative official Hemadri Pandit, which employed dry masonry construction using precisely interlocked black basalt stones without mortar.

While no major temples directly attributed to this period have been identified specifically within Kalmeshwar town, the broader Vidarbha region experienced intensive temple construction during the Yadava epoch, with this architectural tradition subsequently adopted during later medieval periods. The Yadava kingdom maintained its authority until the early 14th century, when invasions by the Delhi Sultanate under Alauddin Khilji's generals led to the annexation of their territories by 1317 CE.

Following the Yadava decline, the Gond kingdom of Deogarh emerged as the dominant political force in the region, with Bakht Buland Shah and his successors establishing administrative structures that laid the foundation for modern Nagpur.

The tradition preserved in historical records suggests that during Akbar's reign in the north, a Chhatri military commander named Jai Singh Rana, who had defeated the Gonds at Parseoni, established himself at Kalmeshwar as a territorial headquarters. His descendants maintained administrative authority over the surrounding country under the hereditary title of Deshmukh, a feudal position that granted them control over agricultural revenue and local order.

The Deshmukh families who held positions at Kalmeshwar during the later Gond period became integral to the local administrative hierarchy.

Before 1821, the area remained sparsely inhabited, with only one or two hamlets existing on the banks of the river, while villages such as Anjini, Waregaon, and Yerkhera occupied portions of the landscape. The structure of power remained localised, dependent upon the authority delegated from regional rulers and the cooperative relationship between Deshmukh families and the ruling establishment.

Maratha Rule and Economic Transformation

The arrival of the Maratha authority in the 18th century transformed the administrative and political orientation of Kalmeshwar within Vidarbha.

Raghoji I Bhonsle, the founder of the Maratha dominion in Nagpur, implemented a systematic consolidation of power that extended Maratha control across the territories previously held by the declining Gond kingdom.

By 1739, Raghoji I had effectively rendered Burhan Shah of Deogarh a state pensionary, thereby subjugating the remnants of Gond authority and establishing the Nagpur Kingdom as a Maratha domain. This transition coincided with intensive temple renovation and construction projects sponsored by the Bhonsle dynasty across their territories.

The Ramtek temple complex underwent reconstruction under Raghoji Bhonsle's patronage, following his vow to establish the temple after his victory over Deogarh forces. The Bhonsles, who traced their connections to the broader Maratha confederacy and shared ancestral ties with Shivaji Maharaj, deployed temple patronage as both a religious duty and a mechanism for legitimising their authority over newly incorporated regions.

The temple-building activity served to assert dominion and secure the loyalty of local populations through the sponsorship of sacred spaces. The religious landscape of Vidarbha during this period became increasingly oriented toward Bhonsle patronage, with multiple temples receiving renovation, reconstruction, or newly established sanctuaries throughout their domain. Kalmeshwar, positioned as a significant taluka within the broader Nagpur Kingdom, benefited from this administrative reorganisation and the security provisions that accompanied Maratha consolidation.

The transformation of Kalmeshwar's economy during the late 18th and 19th centuries reflected both its location within emerging trade networks and the development of its agricultural potential. Historical records from the early 19th century describe Kalmeshwar as an important weaving town where the production of cloth constituted a significant economic activity.

The textile traditions of the region had deep historical roots, with hand-woven fabrics representing a specialised craft that employed considerable portions of the local population. The weaving tradition extended across adjacent areas, including Dhapewada, where the Halba Koshti community maintained specialised knowledge of textile production using traditional looms. The distinctive Patti Kinar sarees produced in this cluster featured intricate designs created through extra-weft techniques, characterised by their plain borders and dot motifs. These sarees, crafted from single-cotton yarn measuring 6.5 metres in length, possessed light weight and cooling properties well-suited to Vidarbha's extreme heat.

The sarees gained recognition for their rustic hues and elegant simplicity, representing a form of textile expression that embodied centuries of accumulated craft knowledge. However, the economic viability of handloom production faced mounting pressure during the colonial period as mechanised textiles from British mills flooded Indian markets, undermining the price competitiveness of hand-woven cloth.

By the end of the 19th century, the income generated from textile production at Kalmeshwar had declined substantially. Census records from 1891 documented Kalmeshwar's population at approximately 5,921 inhabitants, which had fallen to 5,340 by 1901. This demographic contraction reflected broader patterns of economic stress affecting weaving communities. The disappearance of reliable markets for handloom cloth disrupted the traditional economic base, forcing many weavers to abandon their craft in search of alternative employment.

The connection between Kalmeshwar and agricultural production, particularly orange cultivation, developed progressively during the 18th and 19th centuries, becoming the dominant economic activity of the region. The Bhonsle rulers, recognised for their agricultural expertise, actively encouraged citrus cultivation by providing land, irrigation facilities, and technical support to farming communities.

The suitability of Kalmeshwar's soil and climate for orange production attracted increasing investment in orchard development. The black soil characteristic of the region and the availability of water resources from the Chandrabhaga River system created favourable conditions for citrus farming. Orange plantations spread across multiple talukas of Nagpur district, including Kalmeshwar, Katol, Narkhed, and Saoner. Among these areas, Kalmeshwar developed a reputation for producing high-quality oranges, with successful growers establishing substantial orchards.

The development of Nagpur as the "Orange City" represented a long-term process of agricultural specialisation driven by climatic advantages, market demand, and consistent investment in orchard infrastructure. The orange trade generated significant commercial activity, with merchants establishing networks to distribute fruit to distant markets. The cultivation practices refined over generations enabled farmers to produce oranges that gained recognition for their superior quality, with distinctive flavour profiles and appearance. By the early 20th century, Nagpur oranges had achieved recognition in domestic markets and generated substantial agricultural revenue for the region.

The arrival of the railway transformed Kalmeshwar's connectivity and commercial possibilities. The Bhopal-Itarsi railway line opened in 1884, providing the initial infrastructure link.

Between 1923 and 1924, the connection between Itarsi and Nagpur Junction was completed, establishing a unified transport corridor through the region. The Kalmeshwar railway station, constructed as part of this network development, became operational on the Bhopal-Nagpur section under the Central Railway division.

The establishment of rail connectivity represented a critical development for agricultural commerce, enabling the transportation of oranges to distant markets across India. The railway provided reliable access to urban centres in northern and southern India, facilitating the expansion of Nagpur's orange trade into regions previously unreachable through road-based commerce.

The infrastructure investment symbolised the British colonial focus on resource extraction and export-oriented development, prioritising connections to ports and commercial centres over internal development.

Electrification of the railway line proceeded in phases, with the Bhopal-Itarsi section undergoing electrification between 1988 and 1989, and the Itarsi-Nagpur section completed in 1990-91. The railway infrastructure enhanced the region's accessibility to industrial opportunities and contributed to patterns of settlement and economic organisation around the rail corridor.

Colonial Period and Industrial Development

During the colonial period and immediately following independence, Kalmeshwar remained primarily an agricultural region with secondary commercial and administrative functions. The British consolidated administrative structures established by earlier regimes, incorporating Kalmeshwar into the colonial district administration.

Following the Battle of Sitabuldi in 1817, the Bhonsle state came under increasingly effective British control.

By 1853, after the death of Raghoji III without an heir, the British directly annexed the Nagpur region, subsequently integrating it into the Central Provinces and Berar administrative structure. Kalmeshwar functioned as a taluka headquarters within this framework, housing administrative offices, a police station, and post offices that connected it to the broader colonial bureaucratic apparatus.

A severe plague epidemic struck the town toward the end of 1906, claiming approximately 1,300 inhabitants and creating a demographic crisis. This catastrophe prompted discussions regarding health and sanitation infrastructure, with subscriptions collected for the establishment of a dispensary to serve the town and surrounding villages.

The post-independence period witnessed the emergence of industrial development in Kalmeshwar as part of Maharashtra's broader industrialisation strategy.

The Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC), established as a separate corporate entity on August 1, 1962, implemented policies of strategic industrial park development across the state. The corporation's foundational decisions regarding infrastructure provision, particularly the development of filtered potable water supply systems of adequate capacity, transformed possibilities for industrial location decisions. MIDC's policy of providing water supply to nearby populations from their industrial supply systems resulted in phenomenal urban growth around industrial areas.

The Kalmeshwar MIDC industrial estate emerged as a significant industrial node within Vidarbha, providing land, roads, drainage facilities, and street lighting to manufacturing enterprises. Steel manufacturing represented a substantial portion of Kalmeshwar MIDC's industrial activity, with multiple metal fabrication units, ferro-alloy workshops, and related metalworking enterprises establishing operations.

At the height of this industrial development, approximately 65 steel manufacturing units operated across Vidarbha, employing between 30,000 and 35,000 workers in facilities located throughout industrial areas, including Butibori MIDC, Hingna MIDC, and Kalmeshwar MIDC. This industrial growth represented a deliberate effort to diversify Nagpur's economic base beyond agriculture.

However, the commercial viability of Kalmeshwar's orange market experienced dramatic transformations beginning in the late 20th century. The combination of expanded production capacity across multiple growing regions, shifting consumer preferences, and logistical challenges created conditions of chronic oversupply.

Approximately 1.5 crore orange saplings were transported from nurseries in Warud, Ubali, Katol, and Nagpur districts beginning in 2004, with total plantings across the wider region reaching approximately 3 crore saplings. Orange trees require five to six years to reach productive maturity, meaning substantial production increases manifested beginning around 2009-2010.

This expansion coincided with the emergence of competing citrus supply from Rajasthan and imported citrus fruits entering metropolitan markets. By 2015, the famous Nagpur orange market had collapsed under the weight of oversupply and diminished demand. Prices plummeted to unprecedented lows, with harvested fruit fetching only one to ten rupees per kilogram, insufficient to cover harvesting costs or transportation expenses.

Unseasonal rains in southern Indian states destroyed market demand in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, which had historically constituted primary destinations for Nagpur oranges. Farmers confronted the crisis of harvested but unsaleable fruit, often forced to abandon their crop along roadsides rather than incur losses through transportation to distant markets. The orange cultivation that had defined the region's agricultural economy for over a century entered a state of profound decline from which recovery proved elusive.

The handloom traditions of the Kalmeshwar region experienced parallel contraction during the same period. The artisanal weaving communities that had persisted through the colonial era and the early independence period faced accelerating decline from the final decades of the 20th century onward.

In Dhapewada, a village historically known for handloom saree production located approximately 20 kilometres from Nagpur within Kalmeshwar taluka, the number of active loom households diminished from approximately 40 functional units to merely six families by the early 21st century.

The Patti Kinar saree tradition that had represented accumulated generations of craft knowledge found no markets among younger consumers, who preferentially purchased machine-made textiles offering lower cost and perceived uniformity.

The mechanisation of textile production had rendered handloom sarees economically uncompetitive in mass markets. Cooperative societies that had sustained weaving communities through institutional frameworks and market linkages struggled to maintain viability as membership declined and sales contracted.

The artisans, predominantly from the Halba Koshti community, continued weaving primarily through habit and cultural attachment rather than economic necessity. The younger generation actively rejected the profession, recognising the absence of sustainable income generation from weaving and migrating to urban centres or seeking alternative employment in service sectors.

The knowledge systems embedded in these textile traditions remained concentrated among ageing artisans, with discontinuities emerging in the transmission of specialised skills to new generations.

Contemporary Developments and Future Directions

Contemporary Kalmeshwar reflects the convergence of declining traditional economies, variable industrial performance, and renewed development initiatives.

The steel manufacturing sector, which had represented a significant source of employment, contracted sharply beginning in the early 21st century. Four major ferro-alloy units, including facilities such as Vidhi Alloys in Umrer, SMTC Power and Industries in Kanhan, Micron Minerals in Butibori, and Sumant Ferroalloys in Gondia, permanently ceased operations as rising power costs rendered continued production uneconomical.

Over 40 mid-sized steel units shut down within Vidarbha across two decades, eliminating approximately 400 direct and indirect employment opportunities in concentrated periods.

The withdrawal of these industrial operations reversed earlier gains in industrial diversification and employment generation.

In 2018, the Central Railway proposed a light hauling base (LHB) manufacturing plant at Kalmeshwar with a proposed investment of 500 crore rupees and projected generation of 700 direct and 2,000 indirect employment opportunities, yet the project relocated to Bhusawal due to land acquisition difficulties, representing a significant setback for regional industrial development.

The town continued to function as a regional administrative centre, with Kalmeshwar serving as the taluka headquarters, housing 51 gram panchayat units coordinating the administration of 108 villages across the taluka.

The telecommunications infrastructure improved substantially, with 16 post offices providing connectivity services. Educational infrastructure expanded, with 90 primary schools operating within the taluka and 4 libraries providing access to resources. Agricultural production persisted as the primary economic occupation for the majority of the population, despite the challenges confronting traditional crops like oranges and the limited availability of surface irrigation facilities. Local farmers maintained roles as primary suppliers of vegetables and milk to Nagpur city, particularly in cabbage production, representing a diversification from earlier mono-crop orientations.

The transition of Kalmeshwar during recent years reflects renewed governmental interest in transforming it into a satellite city of Nagpur. Large-scale infrastructure projects announced in 2025 include the construction of a 536-metre railway overbridge at level crossing no. 289 under the Setubandhan Yojana at a cost of 55 crore rupees, intended to eliminate traffic disruptions caused by frequent railway gate closures.

The overbridge represents a response to persistent traffic congestion affecting movement between Nagpur and areas north of the railway line. A complementary One-Time Improvement scheme allocating 96 crore rupees targets the development of 9.5 kilometres of internal roads, incorporating modern infrastructure, including dividers, white-topped surfaces, drainage systems, pedestrian pathways, bus stops, and street lighting.

These developments signal a recognition that Kalmeshwar requires fundamental infrastructure improvements to support its role as a growing satellite settlement. The Dhapewada textile cluster, located within Kalmeshwar taluka, which had experienced nearly three decades of decline, attracted renewed attention from the National Institute of Fashion Technology at Mumbai, with research teams visiting in 2025 to assess possibilities for revival.

Training initiatives by organisations, including the Purti Group, began engaging 250 women in weaving skills during 2025, representing incipient efforts to revive the craft knowledge embodied in the Patti Kinar tradition.

These interventions acknowledged the cultural and historical significance of textile production while attempting to create economic sustainability through contemporary market linkages and design modernisation.

The historical trajectory of Kalmeshwar reveals a place where successive economic specialisations have risen and declined across different temporal epochs. The Iron Age megalithic communities that left cairn circles and burial monuments gave way to medieval temple construction networks and administrative reorganisation.

The weaving traditions that sustained populations through centuries faced mechanised competition during the colonial era. The orange cultivation that succeeded weaving as the defining agricultural commodity experienced collapse from overproduction.

The industrial development that diversified the economic base contracted sharply during the early 21st century. Each transition involved the disruption of existing patterns and the reorganisation of economic relationships.

The contemporary moment presents Kalmeshwar as a place of infrastructural investment and renewed development initiatives, yet grounded in a longer history of adaptation and transformation.

The region's archaeological resources remain substantial, with megalithic sites, Iron Age settlements, and medieval religious architecture continuing to embed historical complexity within the landscape. The agricultural communities that continue to derive livelihoods from cultivation represent continuity with patterns established centuries earlier, even as specific crop selections, technologies, and market conditions have undergone dramatic transformation.

The handloom traditions preserved among ageing artisans represent repositories of accumulated knowledge that face discontinuity without active intervention to maintain transmission to succeeding generations.

The contemporary development initiatives that focus on infrastructure modernisation and satellite city development indicate recognition that Kalmeshwar possesses potential for renewed significance within the regional economy, yet these initiatives remain early in their implementation.

References

Bhat, A., & Sahu, P. (2025). Iron Age settlements and archaeological evidence from Vidarbha region. Nagpur University Department of Ancient Indian History, Culture and Archaeology.

Bogart, D. (2011). Railways in colonial India: An economic achievement? Journal of Economic History, 71(2), 375-412.

Down to Earth. (2024, October 11). Climate change threatens Nagpur oranges: Can this heritage crop survive? Retrieved from Down to Earth publication.

Gazetteers, Maharashtra Government. (1999). Central Provinces District Gazetteers. Government of Maharashtra Publications.

Joshi, N. (2025, February 15). Reviving Vidarbha's Patti Kinar saree as next in line for heritage textile revival. Times of India.

Krishnan, K., & Roy, O. (2015). Understanding the megalithic landscape of Ubali, Kalmeshwar taluka, Nagpur district. Heritage University of Kerala.

Kulkarni, R. (2024, August 12). Comprehensive guide to visiting Kalameshwar, Maharashtra, India. Audiala Travel Guide.

Nagpur Housing. (2025, October 27). Kalmeshwar development plan: The next real estate hotspot near Nagpur.

Nagpur Today. (2015, November 30). Farmers in deep distress: No takers for oranges in Vidarbha.

Pandey, S. (2025, November 5). Vidarbha's industrial value chain breakdown: Why rich raw materials fail to translate into local growth. The News Dirt.

Ranade, V. (2023, April 27). Ramtek: The Ramayana footprint in Vidarbha. Indi Tales.

Roy, M. A., Soomro, M. A., & Akhlaq, M. W. (2022). British Indian railways: The economic wheel of colonisation and imperialism. BB E Journal, 4(1), 895-950.

Sanvad Setu, DCO Nagpur. (2025, January 31). History and culture.

Shinde, A. (2025, July 21). Trivikrama temple of Ramtek: 5th-century marvel of Vidarbha architecture. The News Dirt.

Testbook. (2023, November 16). Yadava dynasty (Seuna dynasty): UPSC notes and historical overview.

The News Dirt. (2025, June 2). Handloom industry in Vidarbha: Tradition amidst decline.

The News Dirt. (2025, November 6). Adasa: Secrets of an ancient Ganesh village unfolded in Vidarbha's Kalmeshwar.

Times of India. (2014, August 9). Dhapewada: A temple of neglect. Nagpur News.

Vahane, V. (2025). Preliminary report on newly explored prehistoric sites in Saoner, Kalmeshwar and Katol taluka, Nagpur district. Department of Ancient Indian History, Culture and Archaeology, Nagpur University.

Wikipedia contributors. (2021, March 22). Kalmeshwar railway station. Wikipedia.

Wikipedia contributors. (2022, February 13). Gonds of Deogarh. Wikipedia.

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, February 3). Kingdom of Nagpur. Wikipedia.

Comments