Malnutrition and Child Deaths in Melghat

- Pranay Arya

- Mar 21, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Feb 12

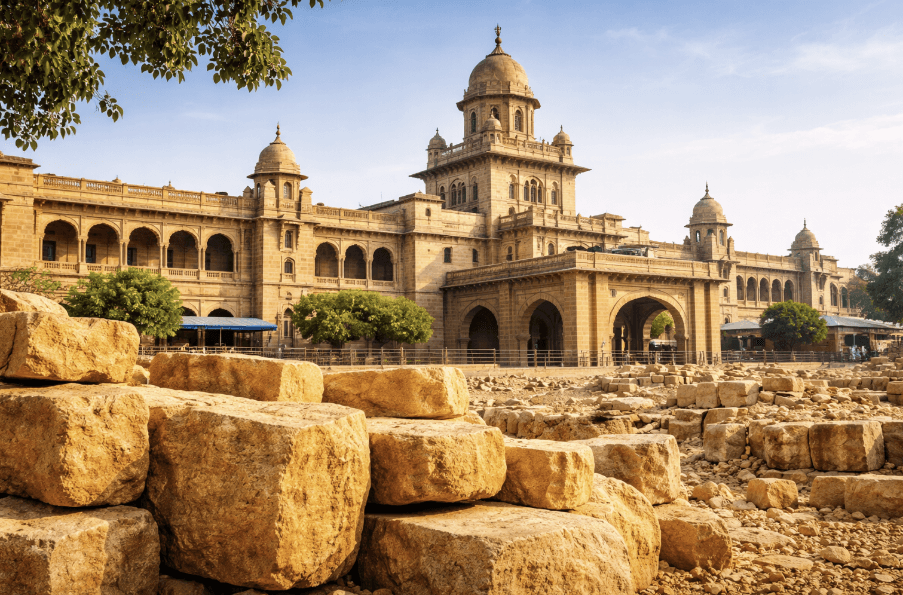

In the heart of Vidarbha's Amravati district lies Melghat, a land where rolling hills and dense forests shape the rhythm of life.

Children here grow up in a world where food is limited, healthcare is distant, and survival is uncertain.

Malnutrition is not a new challenge, yet it remains unresolved, affecting one generation after another.

The numbers tell a story that rarely reaches the headlines, but those living through it feel its impact every day.

A Land of Forests and Fragile Lives

Melghat is home to roughly 250,000 people, mostly from the Korku Adivasi community, who live in small villages like Dharni and Chikhaldara. The forest here is a lifeline, offering wood, wild fruits, and a sense of isolation that cuts both ways. For many, it’s a shield from the outside world, for others, it’s a barrier to help when they need it most.

Life here revolves around the basics of farming small plots, gathering from the wild, and hoping the rains come on time. But the numbers tell a different story, one that’s been tracked for years.

Back in 2012, a study in Dharni found that over half the children aged one to five, 54%, to be exact were so underweight they fell into the severe or moderate category.

That was a signal of something deeply wrong. Older kids weren’t faring much better, with 67% of those aged five to ten tipping the scales too light. Even teenagers and adults showed signs of hunger’s long reach, with 54% of adolescents and up to 25% of older adults undernourished.

What’s behind this? It’s not a single culprit but a mix of factors that stack up like a deck against these families.

The food here is mostly cereals and pulses, think rice, wheat, and lentils, eaten by nearly every household. In winter, people consume about 487 grams of cereals a day. In summer, it climbs to 525 grams. Pulses hover around 88 to 93 grams daily.

It sounds like enough to fill a belly, but the variety stops there. Green leafy vegetables, packed with vitamins, are scarce, 33 grams a day in winter, dropping to a measly 15 grams in summer. Meat and fruit are even rarer. Most families get by on what they grow or find, and when the monsoon fades, so do options like home-grown spinach or fenugreek from kitchen gardens.

Then there’s the way kids are fed. Many parents, stretched thin by work and worry, rely on habits that don’t quite meet a child’s needs such as early weaning or skipping meals when food runs low.

Government programmes try to step in, with 76% of households getting cheap grains through the Public Distribution System and 58% of pregnant women using Anganwadi centres for extra nutrition.

But it’s a patchy fix. Only 12% of kids eat at these centres.

Most take food home, where it might not stretch far enough. In Melghat, hunger isn’t loud, it’s a quiet weight that settles in over time.

The Price of Growing Up Too Soon

If malnutrition is the shadow over Melghat, child mortality is its sharp edge. Back around 2012, government reports pegged the under-five mortality rate in Dharni at 70 per 1,000 live births.

That means for every thousand babies born, 70 didn’t make it to their fifth birthday.

It’s a number that sticks with you, higher than many parts of India at the time, and a stark reminder of how fragile life can be here.

Fast forward to recent times, and the picture’s murkier. District-wide data from 2019-2021, pulled from the National Family Health Survey, shows Amravati’s under-five mortality at 23 per 1,000 live births.

A drop that suggests progress. But zoom into Melghat, and local voices paint a grimmer scene. In 2023, a report from The Hitavada noted 157 infant deaths over ten months, alongside 71 maternal deaths.

Crunching those numbers against an estimated 3,354 births in that period, you get an infant mortality rate closer to 47 per 1,000 live births, double the district average. Think of it like this, if 3,354 babies are born in 10 months and 71 mothers don’t make it, that’s about 2% of births ending in a mother’s death. Scale that to 100,000 births, and you’re at 2,117 deaths, a brutal toll. It’s like every village losing a mother or two each year, which ripples through families and neighbours. It’s not a perfect calculation, but it hints at a gap between the broader stats and what’s happening on the ground.

Why are kids still dying? Malnutrition plays a big role. A child who’s underweight or wasting, where their weight drops dangerously low for their height, is more likely to fall ill.

In Melghat, wasting hit 26.2% of under-fives in 2019-2021, up from 24.7% a few years earlier. Severe wasting, the kind that leaves a child skeletal, climbed to 10.7%. These kids face infections like pneumonia or diarrhoea with little strength to fight back.

Spotty healthcare facilities like Kalamkhar’s Primary Health Centre are often understaffed or hard to reach.

Mothers aren’t escaping this either. That 2023 report flagged a maternal mortality rate that, if annualised, could reach over 2,000 per 100,000 live births, far above India’s national average.

It’s an outlier that might reflect miscounting or a spike in crises, but it underscores the truth that when mothers and babies struggle, the whole community feels it. In Melghat, losing a child is a risk woven into everyday life.

Signs of Change, Shadows of Struggle

Things aren’t standing still. The National Family Health Survey offers a glimpse of hope, or at least movement.

Between 2015-2016 and 2019-2021, stunting in Amravati’s kids under five fell from 38.1% to 29%.

That’s fewer children growing up shorter than they should, a win tied to better feeding programmes and awareness.

But the same survey shows underweight kids rising from 33% to 38%, and wasting ticking up too.

It’s a puzzle, one problem eases, and others dig in deeper.

Local efforts keep pushing. Anganwadis hand out meals or rations, and some villages have seen health workers step up checks on kids’ growth.

In 2021, a piece from Down To Earth quoted a Dharni official saying infant mortality had dipped to 37 per 1,000 live births over a year, not far off the 2023 estimate. It’s progress, but it’s slow, and the numbers still lag behind what you’d hope for.

What’s holding things back? Access is a big one. Roads to clinics can turn to mud in the rains, and staff shortages mean a nurse might cover dozens of villages.

Then there’s culture, habits like giving babies watered-down milk instead of breastmilk, or skipping veggies because they’re not around.

Poverty keeps families locked in, too. A day’s wage might buy grain but not medicine. It’s not that people don’t care, they’re just stretched to breaking.

Compare this to the past, and you see shifts. That 54% underweight rate from 2012 hasn’t been matched in recent surveys, but 38% in 2019-2021 isn’t a victory.

It’s a sign the fight’s far from over. Mortality’s the same, 70 per 1,000 in 2012 versus 47 or so today in local counts. Better, yes, but not good enough when every digit’s a child who didn’t make it.

Melghat’s story isn’t one you’ll find splashed across front pages, but it lingers once you hear it. There’s something about this place, its hills, its people, its quiet battles, that pulls you in and won’t let go.

It’s not about pointing fingers but seeing what’s real for those living it. The numbers shift, the efforts grow, and yet the forest stays silent, holding its secrets close.

Maybe that’s what keeps us coming back to places like this, not to solve them, but to understand them, one step at a time.

References

Birdi, T. J., Joshi, S., Kotian, S., & Shah, S. (2014). Possible causes of malnutrition in Melghat, a tribal region of Maharashtra, India. Global Journal of Health Science, 6(5), 164-173. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4825484/

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. (2021). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-2020: State Fact Sheet - Maharashtra. Mumbai: IIPS. https://rchiips.org/nfhs/factsheet_NFHS-5_MH_en.pdf

Nutrition Group IIT Bombay. (n.d.). NFHS-4 vis-a-vis NFHS-5: Progress in Maharashtra on key indicators. https://www.iitbnutritiongroup.in/nfhs-4-vis-a-vis-nfhs-5-progress-in-maharashtra-on-key-indicators/

The Hitavada. (2023, April 8). Infant, maternal mortality up in Melghat. The Hitavada. https://www.thehitavada.com/Encyc/2023/4/8/Infant-maternal-mortality-up-in-Melghat.html

Thomas, T. (2021, July 27). Fixing severe child malnutrition: Views from Amravati’s Dharni. Down To Earth. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/health/fixing-severe-child-malnutrition-views-from-amravati-s-dharni-78013

Comments