Heritage Wells of Vidarbha: Forgotten Water Structures Across Time

- Pranay Arya

- May 22, 2025

- 5 min read

Wells across Vidarbha were once dug with care, layered in stone, and built to last centuries. Today, many of them remain unknown to most of the public. These are not simple pits for drawing water, they are structures with carved entrances, chambers underground, and engineering suited for a region where water has always been scarce.

Some stand hidden under encroachments, others are filled with waste. A few have drawn renewed attention. Most have not.

These included stepwells known locally as bavadis or pairyachi vihirs, which often featured stone staircases, galleries, and resting chambers. They were used for everything from collecting water to conducting rituals, social gatherings, and agriculture. In Vidarbha’s dry months, these structures ensured villages and cities could sustain life.

From the 14th century Maratha period through British rule and into the early 20th century, the building of wells remained a civic priority. Kings, temple authorities, village heads, and even freedom movement leaders like Mahatma Gandhi oversaw their construction.

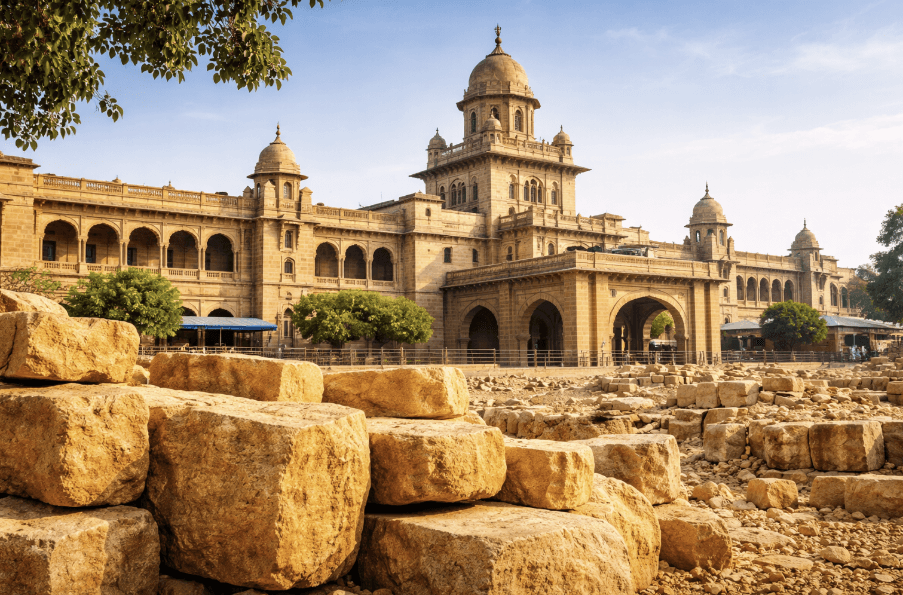

The region’s geography made these wells not only functional but critical to survival. Their architecture reflected that. Designs incorporated descending steps, thick stone walls, and open chambers for ventilation. Many had decorative arches or carved shrines, especially those attached to temples or pilgrimage routes.

Structures in Stone

Vidarbha’s heritage wells were often built to last through droughts and monsoons. They were designed with wide steps that reached the groundwater level, allowing for year-round access.

Some of the best-preserved examples reveal how these wells doubled as architectural statements. Their walls featured toranas, columns, and carved panels. Openings were oriented for airflow, and many included pavilions or niches to provide shade.

The Ganesh Kund in Wela Harichandra village, on the outskirts of Nagpur, was built over 600 years ago by the Bhonslas.

The structure is octagonal, with multi-tiered steps and carved stone walls. Local students rediscovered the site in 2018, but its arches and stairs have since begun to collapse. There are no protective measures in place.

In Sitabuldi, the Buty Baoli is officially listed as a Grade I heritage site. This deep stepwell with arched entrances was once surrounded by open land.

A private commercial project in 2022 covered the structure with shops and scaffolding. Conservation orders were issued, but the well remains buried from public view.

The Mahimapur stepwell in Amravati was constructed during the Yadava dynasty, likely in the 13th century.

It is a large seven-storey structure with 85 steps. It contains carvings from that period and has been the subject of a recent conservation study. Some restoration work has been completed. It is now being promoted not only for its heritage value but also as a site for groundwater recharge.

In Wardha’s Kelzar village, a stepwell linked to a temple was uncovered in 2018. It has dual staircases and is believed to date to the Bhonsla era. The structure is intact, but the local community struggles with water shortages. The temple trust has expressed interest in using the well as a functional reservoir, though official support is limited.

One of the most documented wells in Vidarbha was dug in 1933 under the direction of Mahatma Gandhi. Located in Borkar Nagar, Nagpur, it was intended for Dalit sanitation workers who were denied access to public wells.

Gandhi inaugurated it during a visit to the city. It still exists, and a plaque marks the site. It remains one of the few public wells linked to the freedom movement.

A different story is found in Gokulpeth’s Nawab Kua. Once a public well used even in peak summer, it has now been reduced to a dumping site. Religious waste, damaged idols, and domestic trash are thrown in regularly. The well is dry year-round, and its historical value has been lost to neglect.

Then and Now: Heritage Wells in Shambles

Heritage wells served as more than just sources of water. They were central to how settlements developed.

It had separate platforms for drawing water for orchards. Others, located in temple courtyards or along trade routes, were used by travellers, farmers, and priests alike.

Nagpur’s historical water system once included canals, pottery pipelines, and stepwells interconnected to supply water to different elevations.

These were not isolated structures but parts of a broader plan to handle seasonal extremes. During conflicts, rulers are recorded to have filled up or sealed off wells so invading armies could not access them.

In some cases, structures were built with symbolic intent. The Gandhi well in Borkar Nagar was both a public utility and a gesture of inclusion. Its construction reflected a deliberate act against untouchability.

It was funded by local residents and remains one of the few wells from the period that is still recognised officially.

Across Vidarbha, there is growing awareness of the need to preserve these structures. In 2024, the Nagpur Municipal Corporation announced a ₹1.52 crore programme to clean and restore 446 old wells across the city. Officials stated that out of nearly 860 such structures, many could be revived to help recharge groundwater. The programme includes desilting, adding protective grills, and ensuring the structures are not encroached upon.

At the same time, reports from field surveys and local journalists confirm that many listed wells remain in poor condition. In Sitabuldi, restoration plans for Buty Baoli have been delayed. In other areas, residents remain unaware that a historic well exists beneath a pile of debris or behind a makeshift stall.

Traces That Remain

In rural parts of Vidarbha, some wells are still in use. They are visited by farmers, used for cattle, or tapped during water shortages. In villages like Mahimapur and Kelzar, there is a push to combine heritage with practical use.

Temple trusts and NGOs have expressed interest in including these wells in village water planning. They argue that maintaining them offers both cultural and environmental value.

There are also efforts by private researchers and students to document heritage wells. One initiative has mapped over 1,800 wells across Maharashtra, including dozens in Vidarbha.

These surveys have included photographs, architectural drawings, and oral histories from residents. While academic documentation is improving, legal protection for most of these sites remains inconsistent.

Not all efforts succeed. The Ganesh Kund in Wela Harichandra remains outside official protection lists.

The Nawab Kua continues to fill with refuse. Without active monitoring, these structures lose their function and disappear from public knowledge.

Still, the physical remains are not easily erased. Thick stone walls resist erosion, even when neglected. Inscriptions survive in fragments. Many of the sites are marked in old land records or temple boundaries, and a few are visible in satellite imagery.

Across Vidarbha, heritage wells offer a clear record of how communities once managed water, built architecture, and created shared spaces. Their design reflected the region’s environment, the needs of its people, and the knowledge of local builders. While some are being reclaimed, many remain beneath layers of neglect.

References

Behl, M. (2018, February 16). 6-centuries-old stepwell ‘found’ in ruins by college. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nagpur/6-centuries-old-stepwell-found-in-ruins-by-college/articleshow/62937689.cms

Behl, M. (2019, February 21). A unique step well and a temple. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nagpur/a-unique-step-well-and-a-temple/articleshow/68087221.cms

Burange, C., Holey, S., & Pande, D. (2023). Mahimapur Stepwell – A Journey Through History, Architecture, Conservation and Documentation. International Journal of Research in Engineering, Science and Management, 6(12). https://journal.ijresm.com/index.php/ijresm/article/view/2875

Ganjapure, V. (2024, August 7). Nagpur’s historic wells to get fresh lease of life, NMC commits ₹1.52cr. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nagpur/nagpurs-historic-wells-revitalization-by-nmc-with-152cr-funding/articleshow/112331573.cms

Ministry of Culture, Government of India. (2023). Mahatma Gandhi Well, Nagpur. Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav Digital District Repository. https://amritmahotsav.nic.in/district-reopsitory-detail.htm?24957

Nikam, K. N. (2024). Stepwells as Heritage Sites: Exploring Their Roles for Sustainable Communities. Ancient Asia, 15(1-2), 103–127. https://doi.org/10.47509/AA.2024.v15i.06

Times of India. (2023, March 23). Heritage panel mum as builder uses Buty Baoli, open space for commercial purposes. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nagpur/heritage-panel-mum-as-builder-uses-buty-baoli-open-space-for-commercial-purposes/articleshow/98923842.cms

Times of India. (2025, May 21). Once a Heritage Well, Nawab Kua Now a Dumping Ground for Waste. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nagpur/once-a-heritage-well-nawab-kua-now-a-dumping-ground-for-waste/articleshow/121299896.cms

Comments