How the Brahmi Script Shaped Ancient Communication in Vidarbha

- thenewsdirt

- Jul 31, 2025

- 8 min read

Ancient stone inscriptions scattered across Vidarbha carry messages from over two millennia ago. The letters etched into pillars, rocks, and cave walls in this central Indian region belong to the Brahmi script, one of the oldest writing systems of South Asia. Far from mere markings, these Brahmi inscriptions reveal how early writing took root in Vidarbha’s society.

They tell of kings and monks, of donated caves and imperial orders, illuminating a rich history that had long remained silent.

This article explores the role and importance of the Brahmi script in Vidarbha, tracing its journey from the 3rd century BCE through the flourishing of Buddhism and the rule of local dynasties, and examining why these ancient writings remain vital to understanding the region today.

Earliest Traces of Brahmi in Vidarbha

The introduction of the Brahmi script to Vidarbha dates back to the Mauryan era, around the 3rd century BCE. The oldest known inscription in Vidarbha was found on a stone slab at Deotek village in Chandrapur district.

Its Brahmi characters closely resemble those of Emperor Ashoka’s edicts, and the text, written in early Prakrit, records a local ruler’s decree forbidding animal slaughter.

This discovery suggests that Mauryan officials or influences had reached Vidarbha, bringing with them the practice of inscribing proclamations on stone. The Deotek inscription’s content is strikingly similar to Ashoka’s messages of ethical governance, indicating that even in this distant province, imperial ideals were being communicated through Brahmi writing.

Not long after the Mauryan period, local rulers in Vidarbha began using Brahmi to mark their own authority. Coins unearthed in the region from the 2nd century BCE bear Brahmi legends naming local kings and cities. For example, a copper coin from ancient Bhadravati (modern Bhandak in eastern Vidarbha) is stamped with the word “Bhadavatiye” in Brahmi script. This simple inscription, meaning “(coin) of Bhadravati”, establishes the town’s identity and its participation in a literate economic network.

Similarly, other coin series from Vidarbha carry Brahmi-inscribed names of rulers ending in bhadra, suggesting a lineage of post-Mauryan chiefs who issued inscribed currency.

The use of Brahmi on coins and seals indicates that writing had quickly become an accepted tool for administration and trade in Vidarbha. Even without paper, the inscribed word travelled on metal and stone, spreading information across the region.

Script of a Buddhist Heartland

By the early centuries CE, Brahmi script was woven into the rise of Buddhism in Vidarbha. The region became a thriving centre of Hinayana Buddhist culture, and Brahmi was the medium through which this heritage was recorded.

At Pauni, an ancient town in Bhandara district, archaeologists have uncovered dozens of donative inscriptions in Brahmi, left by Buddhist devotees.

Carved on pillars and slabs around what was once a large stupa complex, these short Prakrit texts mirror the inscription styles of famed Buddhist sites like Sanchi and Bharhut. They typically mention the names of donors and the objects or structures they gifted (such as caves, cisterns, or portions of railings).

The fact that so many Brahmi inscriptions were found at Pauni confirms that Vidarbha was fully integrated into the Buddhist monastic network by the 2nd–1st century BCE. Monks and lay followers in this region used writing to record their piety, just as their counterparts did in central India. The script provided a common cultural thread, allowing ideas and practices to circulate widely.

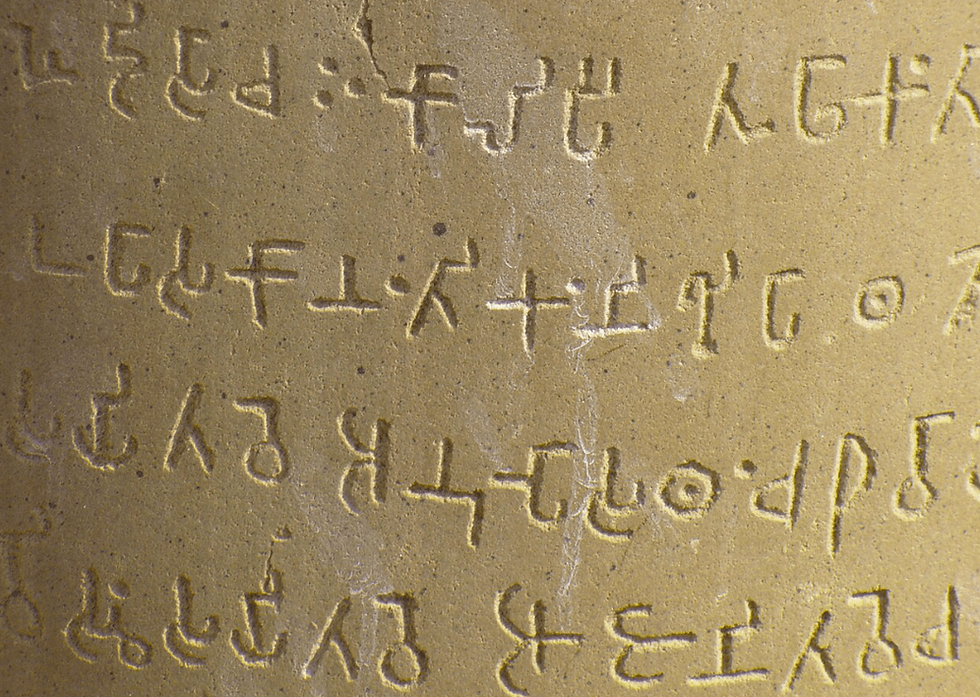

A stone pillar from Pauni in Vidarbha bears a 2nd-century CE Brahmi inscription referring to the “Great Satrap” Rupiamma. This inscribed pillar, now in a museum, marked the extent of a Western Kshatrapa ruler’s influence in the region.

The clearly carved Brahmi characters illustrate how imperial and religious messages alike were recorded in stone for posterity.

Vidarbha’s rocky hills also hold Brahmi-inscribed cave complexes that speak to the spread of Buddhism. In western Vidarbha, the city of Bhadravati (ancient Bhandak) has a set of rock-cut Buddhist chambers at Vijasan Tekdi, dated to roughly the 2nd century CE.

A dedicatory Brahmi inscription there links the excavation of these caves to the reign of the Satavahana king Yajna Shri Satakarni.

This suggests that during Satavahana rule, local patrons in Vidarbha commissioned cave shrines and recorded their deeds in writing, much as was happening in the western Deccan.

The Bhadravati caves, the largest early Buddhist complex in Vidarbha, preserve Brahmi script on their walls, silently attesting to the patronage that connected this region to a broader religious florescence.

Other examples dot the map. In the forests near present-day Nagpur, the Chandala hill caves harbour two fragmentary Brahmi inscriptions believed to date to the 1st or 2nd century BCE. Discovered in 1971, these inscriptions are among the earliest records in Nagpur district. They are short and partly damaged, but scholars have interpreted personal names and references to a Buddhist establishment within them.

Their significance lies in sheer antiquity. The Chandala inscriptions show that by the late pre-Christian era, people in the heart of Vidarbha were already engraving their language onto cave walls.

According to archaeologist Nishant Zodape, the Chandala cave epigraphs are “very important for reconstruction of the history of Vidarbha,” offering rare contemporary evidence of the region’s early culture.

Each such inscription is a precious data point – confirming, for instance, that Buddhist viharas existed along ancient trade routes that crossed Vidarbha.

Likewise, at the site of Adam in Nagpur district, an earthen stupa has yielded Brahmi inscriptions on relic containers, again tying Vidarbha into the widespread Buddhist landscape. Even in distant Nashik and Karla caves (in today’s western Maharashtra), donative inscriptions make mention of donors or monks from Vidarbha.

These written records underscore that Vidarbha was not an isolated frontier, but an active participant in the spiritual and commercial currents of ancient India. Through the Brahmi script, ideas from the Mauryan heartland, the Satavahanas, and Buddhist sanghas all found a voice in Vidarbha’s terrain.

Royal Edicts and Administrative Records in Brahmi Script

Brahmi script in Vidarbha was not used solely for religious purposes, it became the vehicle for secular and political record-keeping as well. By the 2nd century CE, foreign dynasts who encroached into Vidarbha left their mark in Brahmi.

A remarkable example is the Rupiamma inscription at Pauni mentioned above. Rupiamma was a Saka (Scythian) great satrap associated with the Western Kshatrapa rulers of Gujarat and Malwa.

His memorial pillar at Pauni, inscribed in Brahmi, suggests that these northern rulers briefly extended their authority deep into Maharashtra. The inscription’s text, still legible in Brahmi, effectively stakes a political claim in writing a concrete sign of how scripts served governance. It also hints that literate officials were on hand in Vidarbha to carve such messages for posterity.

As time went on, regional dynasties in Vidarbha relied on Brahmi for official proclamations. The Vakataka kingdom (3rd to 5th century CE), which had its power base in Vidarbha, produced numerous inscriptions on copper plates and stone.

These records, typically written in Sanskrit but using the Brahmi script, document land grants, royal lineages, and temple foundations.

At Borgaon in Wardha district, for instance, archaeologists found a set of Vakataka-era copper plate inscriptions buried near an ancient brick house complex.

The plates, inscribed in Prakrit language and Brahmi script, detail donations of land to individuals and temples, placing Borgaon firmly within the Vakataka administrative system.

Such finds reveal that even smaller towns kept written charters for legal transactions. The Brahmi letters on these copper sheets have survived for sixteen centuries, allowing modern historians to reconstruct revenue systems and governance in Vidarbha’s past.

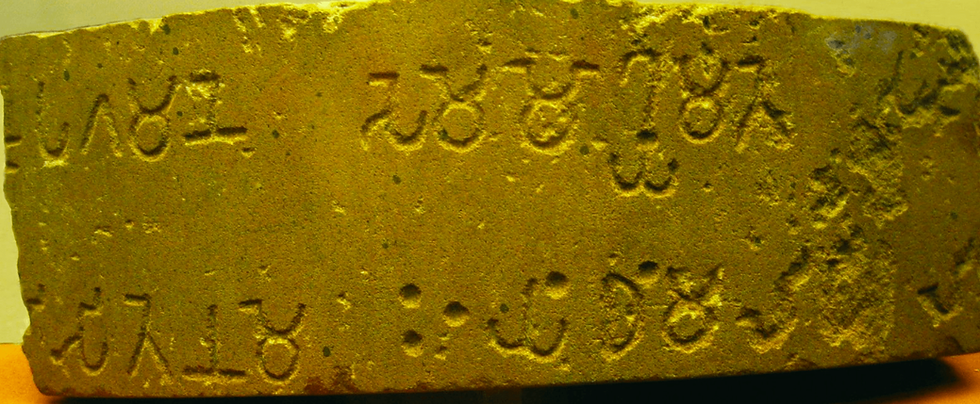

Another illustrative find comes from Rāmtek in Nagpur district, where a lengthy stone inscription was discovered in a temple wall.

This inscription, dating to the 5th century CE, was composed during the Vakataka reign and is incised in 15 lines of Sanskrit using late Brahmi characters. It was essentially a eulogy that recorded the building of a Hindu temple (dedicated to Narasimha) by a Vakataka queen, and it carefully lists the genealogy of the Vakataka dynasty along with ties to the imperial Gupta family.

Though parts of the inscription are damaged, what remains legible has proven to be a key historical document for Vidarbha. It confirms, in elegant courtly verse, the marriage alliances between the Vakataka rulers of Vidarbha and the Gupta emperors of north India. Here again, the Brahmi script was the chosen medium to immortalise political narratives and cement the legacy of kings.

From the humid caves to open fields and temple courtyards, one finds that wherever authority needed to assert itself or religion sought patronage, the Brahmi script was there in Vidarbha, chiselled into rock or pressed into copper, carrying messages through time.

Inscriptions were often carved directly onto stone surfaces. This image shows a section of a 5th-century Sanskrit inscription at Ramtek in Vidarbha, written in late Brahmi script. Such epigraphs documented royal genealogies and religious endowments. The enduring Brahmi lettering seen here has enabled historians to piece together the Vākāṭaka dynasty’s history and its links with the Gupta Empire.

Deciphering the Past and Its Significance Today

The Brahmi script’s importance for Vidarbha goes beyond its ancient utility. Today, it is a primary source of knowledge about the region’s history. Modern scholars were able to unlock these inscriptions only after the Brahmi script was deciphered in the 19th century (a breakthrough achieved by James Prinsep in 1837).

Once the script’s characters and sounds became known, Vidarbha’s stones began to speak.

Researchers have since read dozens of inscriptions across the region, extracting names of forgotten rulers, dates of events, religious affiliations, and details of socio-economic life. For example, the inscriptions at Pauni and surrounding sites helped establish that Vidarbha was an important Buddhist stronghold from the 3rd century BCE onwards.

Likewise, copper plate charters found in places like Riddhapur, Bhandak and Washim have filled gaps in the chronology of local kings. Each inscription is like a puzzle piece that, when put together, transforms the understanding of Vidarbha from a blank spot on the map to a region with a distinct and well-documented historical trajectory.

The content of these writings also underscores Vidarbha’s connectivity. When we read a Brahmi inscription in a cave or on a pot in Vidarbha, we often find references to distant lands and peoples, be it a Mauryan Emperor’s edict, a Satavahana prince’s name, or a Central Asian Saka ruler’s title.

This reveals that Vidarbha was never truly isolated. The script served as a conduit through which imperial policies, religious doctrines, and economic systems flowed into the region. In turn, local innovations in coinage or temple-building were recorded and shared in the same script, contributing to the subcontinent’s cultural mosaic.

Historians point out that these epigraphic finds challenge any notion of Vidarbha as a peripheral backwater. Instead, what emerges from the Brahmi records is a picture of a land actively engaged in broader Indian civilisation, a meeting point of northern and southern influences, where traders, monks, and settlers converged.

The preservation and study of Brahmi inscriptions have become important for Vidarbha’s contemporary identity. Many of the inscribed stones and copper plates are now displayed in regional museums such as the Nagpur Central Museum, bringing pride to locals who can see tangible proof of a rich heritage.

Efforts by the Archaeological Survey of India and scholars from Nagpur University have been directed at documenting these inscriptions before they weather away. There is an ongoing race against time and the elements, especially for those carvings still left in the open.

In recent years, community groups and historians have raised awareness about protecting sites like the Chandala caves and the stupa remains at Pauni and Adam, precisely because the inscriptions there are irreplaceable historical records.

The Brahmi letters etched in Vidarbha’s soil have survived for centuries; they connect the people of this region to an ancient continuum. Deciphered and understood, they ensure that Vidarbha’s story is heard loud and clear in the historical narrative of India.

References

Zodape, N. S. (2022). Study of Prakrit Inscriptions Deotek and Chandala Forest Rock-Cut Cave from Vidarbha Region, Maharashtra. Shodh Samagam, 5(1), 298–303. https://shodhsamagam.com/uploads/issues_tbl/Study%20of%20Prakrit%20Inscriptions%20Deotek%20and%20Chandala%20forest%20Rock-Cut%20Cave%20from%20Vidarbha%20Region,%20Maharashtra.pdf

Bhandare, S. (2019). Early Buddhist Art in Deccan: The Numismatic Underpinnings of Chronology and Political Backdrop. In C. Luczanits (Ed.) Proceedings of the Conference “Crossing Boundaries: International Symposium on the Silk Road”. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:4ea809eb-b04d-4767-8bab-94ca294ed136

The NewsDirt. (2025). 10 Notable Archaeological Finds in Vidarbha. https://www.thenewsdirt.com/post/10-notable-archaeological-finds-in-vidarbha

The NewsDirt. (2023). Bhadravati’s Hidden History: From Ancient Caves to Today’s Vidarbha Town. https://www.thenewsdirt.com/post/bhadravati-s-hidden-history-from-ancient-caves-to-today-s-vidarbha-town

Wikipedia. (2023, June 2). Pauni. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pauni

Wikipedia. (2023, Dec 5). Ramtek Kevala Narasimha temple inscription. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramtek_Kevala_Narasimha_temple_inscription

Comments